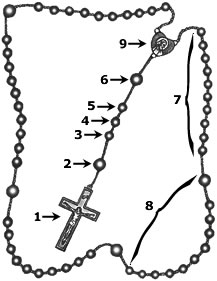

This Chaplet is an adaptation of the Chaplet of Divine Mercy which is organised around the Decalogue (the 10 Commandments) and the episode of the healing of Blind Bartimaeus in Mark 10.46-52. If you have a standard set of Rosary beads you will simply pray through the beads twice. Of course, pause for thoughtful reflection at any time. If you are praying with others the italicised ‘me’ may be pluralised.

1. Pray the Sign of the Cross

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Then,

The Apostles’ Creed

I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, His only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; He descended into hell; on the third day He rose again from the dead; He ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there He will come to judge the living and the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and life everlasting. Amen.

2. Our Father

Our Father, Who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name; Thy kingdom come; Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil, Amen.

3-5. Trisagion

Holy God, Holy Mighty One, Holy Immortal One, have mercy on me and on the whole world.

6. Psalm 51.7

“The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.”

Rehearse the first commandment (below) and then,

7. “Jesus, Son of David / have mercy on me” on the 10 small beads of each decade

8. The Decalogue on the ‘Our Father’ beads which separate each decade.

- I am the LORD your God; you shall not have strange gods before me.

- You shall not take the name of the LORD your God in vain.

- Remember to keep holy the LORD’s Day.

- Honor your father and mother.

- You shall not murder.

- You shall not commit adultery.

- You shall not steal.

- You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

- You shall not covet your neighbor’s wife.

- You shall not covet your neighbor’s goods.

9. Conclude with Mark 10.51-52

“Jesus asked, “What do you want me to do for you?” He said, “Lord, let me receive my sight.” And Jesus said to him, ‘Receive your sight; your faith has made you well.” And immediately he received his sight and followed him, glorifying God…'”

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit. As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end. Amen.

10. Optional Closing Prayer (any appropriate prayers for Divine Mercy may be prayed here).

Eternal God, in whom mercy is endless and the treasury of compassion — inexhaustible, look kindly upon us and increase Your mercy in us, that in difficult moments we might not despair nor become despondent, but with great confidence submit ourselves to Your holy will, which is Love and Mercy itself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.